I am posting this here, on 20/03/17, as I cannot find a copy elsewhere on the web. This is the text of a speech I gave while I was national coordinator of NO2ID at a CAOS (‘Combining All Our Strengths’) meeting convened by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, I think – certainly one of the Joseph Rowntree family of organisations.

For convenience, I have highlighted in red below my articulation of the concept of “informational privity”, which Guy and I had been discussing for a while at this point, which – as the footnote records – I edited shortly after giving the speech, before submitting a copy of my text to the organisers of the meeting.

[In passing, it is interesting to note that much of the thinking that underpins our work at medConfidential appears to have been pretty well developed by this point.]

Rowntree’s Governance Seminars: The Database State

I’m billed this afternoon as talking about ‘ID cards and the NIR’ but as it was my colleague, NO2ID’s general secretary, Guy Herbert, who coined the phrase ‘the database state’ back in 2004 when we were all setting up the public campaign, and this is a database state seminar, I hope you’ll afford me some leeway.

What do we mean by the database state? Simply, that tendency to try to use computers to manage society by watching people.

This afternoon I don’t so much want to talk about the problem – which I think we all acknowledge – but rather to focus on what is being sadly, and sometimes deliberately, overlooked in the so-called debate around compulsory state identity management and related initiatives.

NO2ID believes the time has come to talk about workable solutions and practical ways forward, though it is vital to note that the Home Office ID scheme, to which we remain implacably opposed, cannot be ‘altered’ to accommodate these proposals. The principles on which the ID scheme is based are fundamentally incompatible and it must be scrapped – and preferably the Identity Cards Act 2006 repealed – before any progress can be made.

The government has lost the argument on pretty much every front, and though it keeps cycling through the same tired excuses, ministers have recently tried to develop a narrative that its vision of the future – the database state – is inevitable [e.g. David Blunkett, re. biometric passports]. That, once started, the process is irreversible [e.g. Meg Hillier, at Labour conference]. That, with almost religious zeal, theirs is the only way forward and anyone who disagrees is at best an accessory to terrorism or paranoid.

It’s simply not true.

Indeed, Sir Ken Macdonald’s [outgoing Director of Public Prosecutions] analysis seems to be that it is the state’s obsession and paranoia driving this forward. Others would say that by taking away our freedoms and fundamentally changing the relationship between citizen and state, the government is actually doing the terrorists’ job for them. For if we end up losing our liberty, have the terrorists not achieved victory?

Our campaign may be named NO2ID but we are far from Luddite, as many of you will know. Our collective technical awareness certainly exceeds that of the Home Office, even when they are spending over £100,000 per day on consultants. And, though negative in name, we are a hugely positive bunch fighting for freedom, privacy and a future where these basic rights cannot be falsely traded off against security, either national or personal.

In the time I have left, I’d like to rehearse for you three possible positive approaches, and briefly try to draw out some basic principles.

The first is the concept of ‘informational privity‘. This is a new idea, which I may have previously explained misleadingly [1]. We are all used to leases of real property, or licenses of copyright, for example, occurring through a chain of contracts each of which gives specific and limited rights to the recipient – and just as clearly gives no rights to those outside the chain. It is natural that someone with rights can get direct redress against an infringer with no rights or someone lower down the chain who exceeds their authority.

Informational privity would be a new sort of enforceable property right, with some of the features of confidentiality, but extending to all personal information. Casual talk of data “ownership” leads to all sort of traps. Were all transfers of Personally Identifying Information (PII) subject to such a right, and functionally constrained thereby – it is important that it should not be possible casually to waive it by contract – then we have the means to build conceptual and technological structures that will far more effectively discipline the use and abuse of personal information.

Note that, perhaps controversially, this approach allows for individuals to assert their own rights, and can be developed by the courts, rather than relying on the foresight, vigilance or funding of regulators. And personal rights are politically harder to interfere with than the scope of statutory bodies. The net result would almost certainly be better data protection and most probably better privacy [2].

This is, after all, our data. It makes sense to give me, the person most motivated to do something as the one who will suffer any effects, the power to protect my data and to seek redress if wronged.

[The Information Commissioner himself freely admits his Office is too underfunded and overstretched to properly prosecute Data Protection. One has only to compare the annual 20p per head of population assigned to regulating DP, FOIA and environmental data with the Health and Safety Executive’s £800 million+ per year – on which even it struggles to keep up – to see that increased regulation is just a money pit.]

The second concept is simply to distinguish between identification (‘identity management’) and authentication (‘identity assurance’) – a crucial distinction that successive Home Secretaries and the so-called Minister for Identity seem wilfully to ignore.

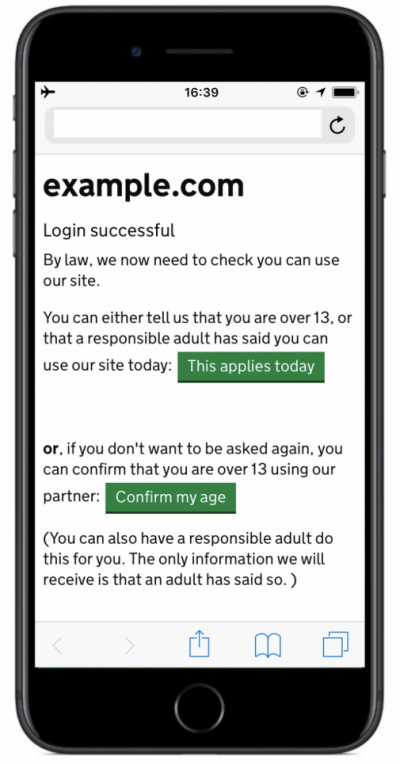

If you need a way to prove something about yourself to a third party, use an appropriate trusted credential which verifies that particular fact.

The requisite technologies are already with us, in the form of digital certificates and encryption. One need give away no more personal information than is actually required for each authentication or verification event [cf. Dave Birch of Consult Hyperion’s ‘psychic paper’], and you are not putting all your eggs into one basket as you would with a National Identity Register – the logic and design of which would put it (and thereby the state) at the centre of every trusted relationship and transaction.

[This is especially true of irreplaceable data such as your biometrics. You only have ten fingers. Why should those unconvicted of any crime be forced to surrender them all to the state? As biometric technologies and markets mature, this is like saying UK citizens should lodge copies of every key they own with the authorities – your front door key, your car key, your computer password, the combination to your safety deposit box.]

In reality, we don’t need to know who someone is in order to be able to trust something about them. It is the paranoia of the database state that says otherwise.

A market of overlapping, interdependent ‘identity tokens’ – maybe even some issued by the government, but on a level playing field rather than monopolistic, bullying basis – could provide the security and trust required to transact in a 21st century society without compromising privacy, liberty or personal security.

The third concept is to precisely target the problem, not broadly prescribe against the symptom. And by this I clearly don’t mean touting around your solution (‘ID cards’) as a salve to all ills. An example of what I do mean, most recently endorsed by the Liberal Democrats but also supported by consumer advocates [e.g. NCC, now Consumer Focus] is ‘credit freezes’, giving each individual the ability to lock their own credit record so that no-one can gain credit in their name.

[Interestingly, NO2ID suggested credit freezes to the Home Office and members of the Home Affairs Committee after Meg Hillier challenged opponents of the ID scheme in the Financial Times in February 2008 to say how they would tackle ‘identity fraud’ without employing features of the Home Office ID scheme. Our suggestion, though we had confirmation at the time that it was received, has been studiously ignored for eight months.]

Credit freezes are a practical solution to a real problem, working effectively in the US and for victims of ‘identity fraud’ in the UK, but it is a radical departure from the database state in that it hands meaningful control over personal information already held by an organisation or group of organisations back to the individual. Credit freezes demonstrate that control can be given to the individual in ways that make the citizen (or consumer, though the two are not synonymous) safer.

If control is the first of my basic principles, then the other two are choice and consent. Without properly attending to all three, you will find it well nigh impossible to build or retain trust – which is absolutely essential for any identity system or infrastructure.

Let us not forget that the so-called ‘voluntary’ ID cards are being imposed by, in officials’ own words, “various forms of coercion” – picking on soft targets who can’t refuse or speak out, bullying those already heavily vetted [airside workers] or duping the young [though they don’t look like they’ll buy it]. The government’s notion of ‘choice’ is at best a perversion of both logic and language.

The intention – indeed the core design principle – has from the outset been universal compulsory registration on the National Identity Register (NIR), whether by designation of documents (e.g. passports or driving licenses) or making it more difficult or impossible to live your life, earn a living, travel, register with a GP, receive benefits or services without submitting to lifelong surveillance and surrendering the master copy of your personal details, and a copy of your only biometric keys to the state.

Citizens who live only at the behest of the state are not free, and any government contemplating “managing the identities” of its citizens would do well to remember that it serves at our pleasure.

Government, like business, must seek our consent – which should always be properly informed. For the last four years, NO2ID has been talking to people, based on Home Office documents, ministerial statements, etc. about what is actually intended and what the consequences might be. And all but one independent poll of which we are aware (not the IPS ‘tracking research’ which polling professionals inform us is a ‘push-poll’) since shortly before the HMRC child benefit disaster show that more people now think ID cards are a bad idea than a good one. Opposition to the database behind the cards is more like 2 to 1 against.

I shall close with a thought, the significance of which has been properly understood, I think – based on their recent public pronouncements – by Sir Ken Macdonald and Dame Stella Rimington.

In an information society, things done to your data can have as much effect on your life as things done to your person.

We have to get this right. And we have to get this right NOW.

In a generation, it may be too late and we’ll be fighting generational battles against the information equivalent of slavery, people trafficking and ‘data rape’. If we get it wrong, we won’t just be living in a surveillance society – our very freedom will be subsumed by the database state.

Phil Booth, 22 October 2008

[1] After speaking at CAOS on 22/10/08, I have taken the liberty of editing this section on informational privity in order to more clearly explain what we consider to be a significant new concept.

[2] There is a distinction. As I keep having to remind people, information security is not data protection is not privacy.